Climate Modelling and Personal Actions to Reduce Our Carbon Footprints

In the last two weeks, I've been reflecting a lot. In August, I moved away from home 'for real' (i.e. not just for an internship) to come to The Hague, Netherlands for grad school. I've been thinking a lot about how I should spend my time, what projects I should work on, and trying to learn about things I haven't yet explored.

People who know me well know that I care deeply about climate change. But, to be honest, I've been trying to stay away from the topic to learn more about other 'grand challenges'. This month's 'Special Report' on 'Global Warming of 1.5ºC' (IPCC, BBC, Reuters) splashed a bit of icy water in my face.

If we, the global human society, want to avoid the onset of irreversible climate change, which will displace millions of people due to sea level rise, drought, and other forms of environmental change we can't adapt to, we have to take drastic action now.

I'm sure these are messages you've heard many times from many people. Some of it sounds scary, and it's natural to be skeptical of such alarming claims. My hope in writing this post is to highlight some things I think are most important for my family, friends, and peers to understand and to remember:

- The science is clear on how climate change is caused by humans. It is uncertain on the timing and magnitude of actual impacts on the climate.

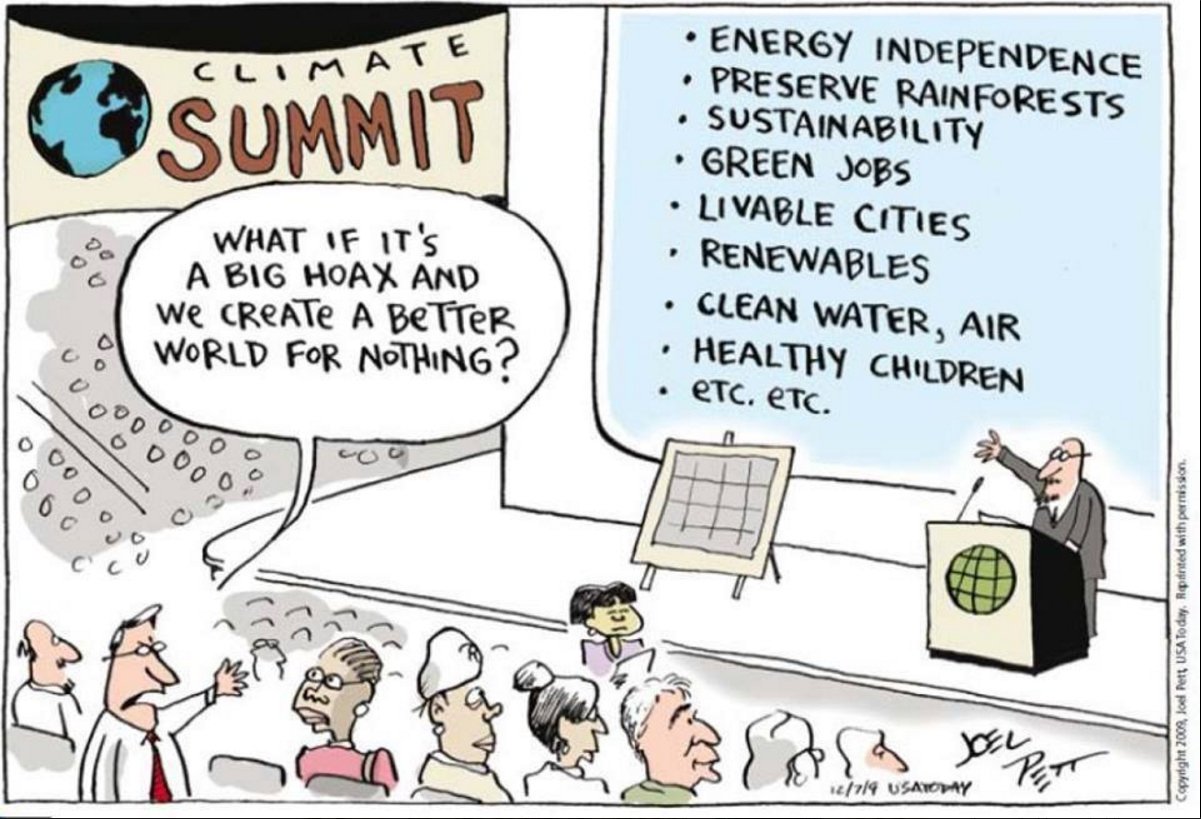

- Regardless of how you feel about climate change, mitigating its worst effects will build better societies and economies.

- Reducing meat consumption really is one big change everyone can make that will make a difference. Flying less is another good idea.

- Canada and Alberta's governing party climate policies are not meeting our obligations, and the opposition is making matters worse.

One more note: earlier, I was wrong about how much I thought air travel is 'worse' than other forms of transportation. While researching for this post, I found evidence that challenged my beliefs, and have adjusted my beliefs accordingly. I hope that you, dear reader, will be equally open-minded to evidence as you read this and in other areas of your life.

Yes, I've watched "An Inconvenient Truth". Yes, I know that some predictions have not come true. And yes, I know that Al Gore flies around the world in planes and probably has a big carbon footprint.

Let's unpack these three statements.

Climate Science

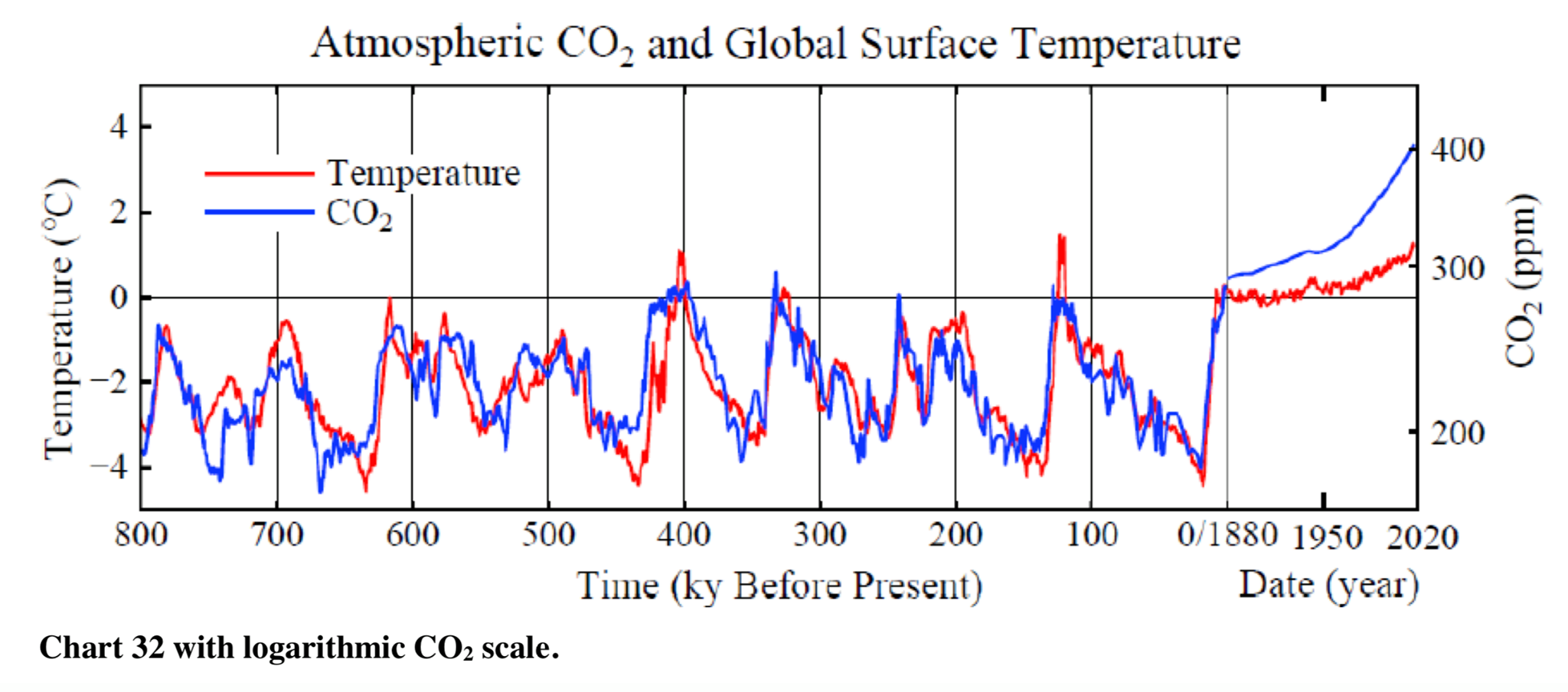

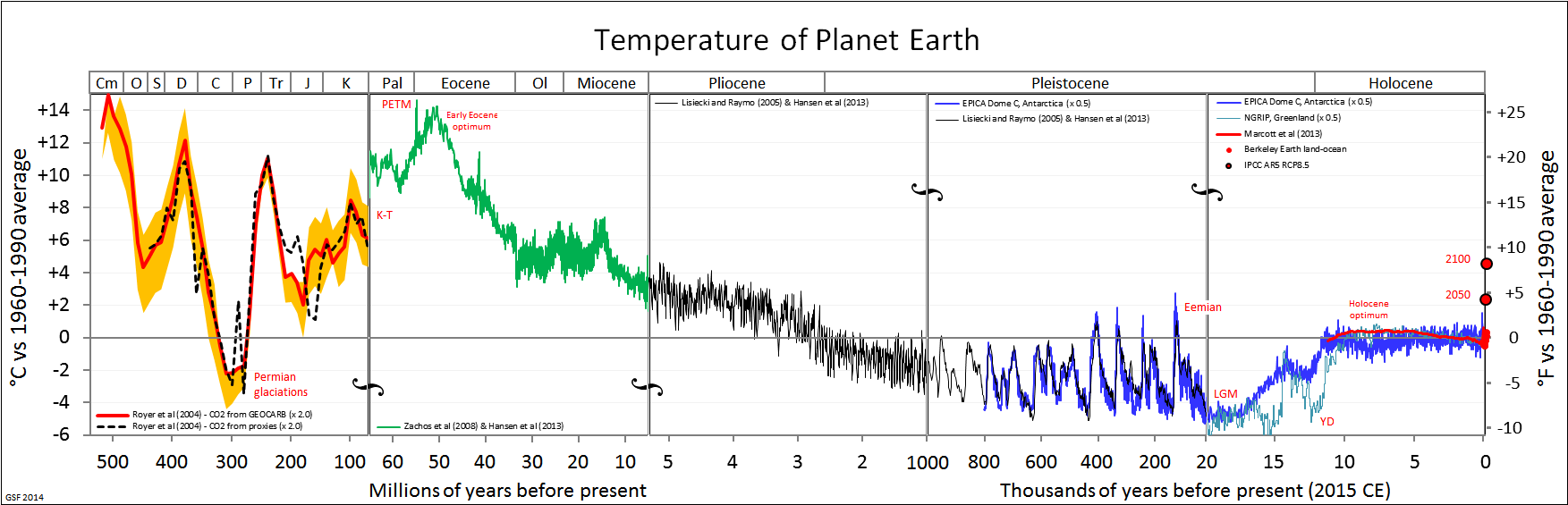

Firstly, the 'hockey stick' graphs that Al Gore showed the 2006 production have continued their trend. Carbon dioxide levels are growing exponentially in a way unprecedented in recent history.

Climate skeptics and deniers have recently been saying that the Earth has been this warm before or that the world operatres in cycles. They forget to mention that "100 million years ago", humans certainly did not have cities all over the world, including many by the ocean.

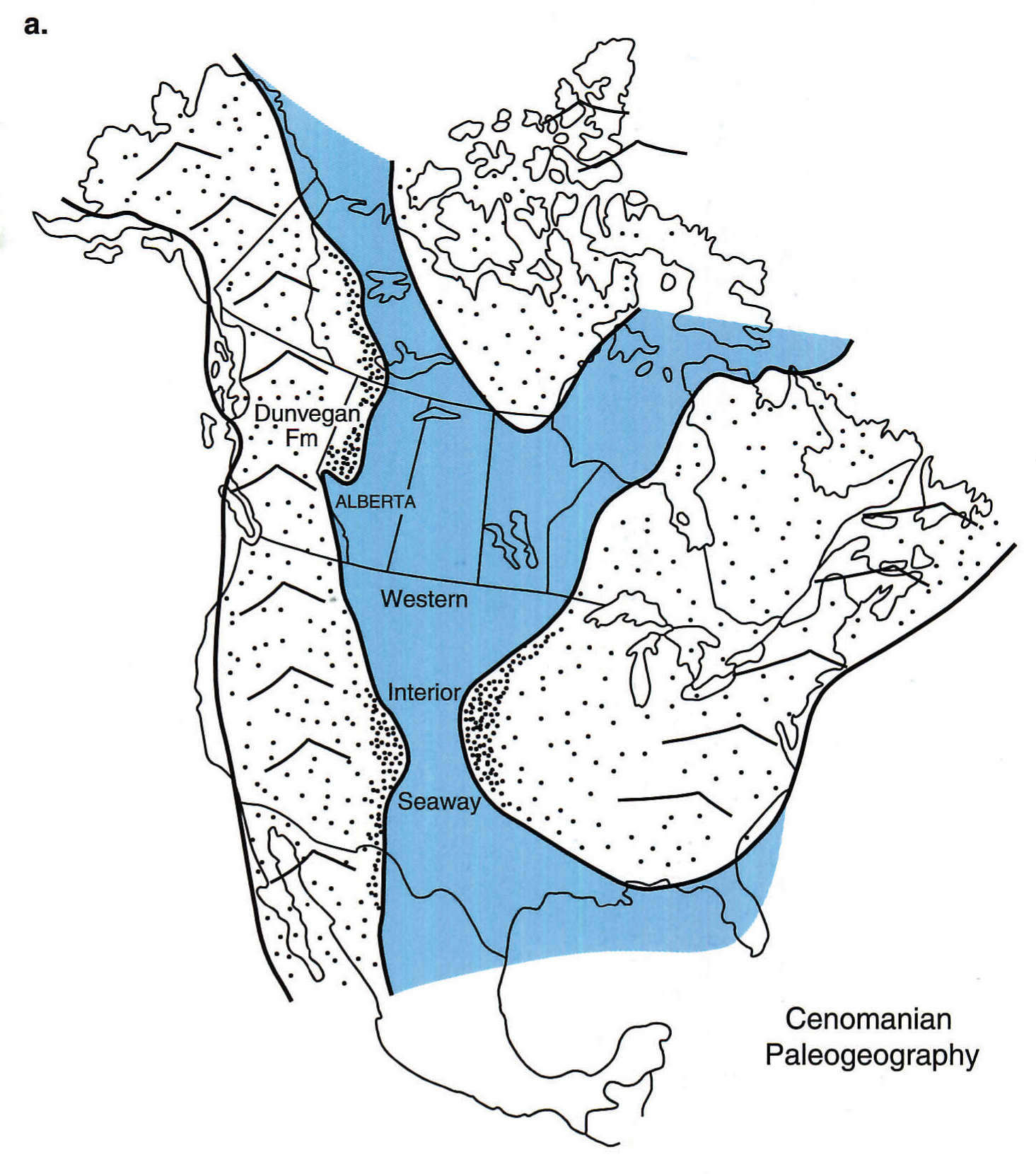

They forget to mention that the T-Rex wasn't even roaming the planet, that India and Madagascar were neighbours, and Alberta was under a 'seaway' that connected the Arctic ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. This seaway is also why today's oil sands and gas reservoirs exist (RAMP Alberta – Fitzgerald, 1978).

Source: Bhattacharya, J.P. (1994). Cretaceous Dunvegan Formation of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin; in Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, G.D. Mossop and I. Shetsen (comp.), Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists and Alberta Research Council. Retreived from http://ags.aer.ca/publications/chapter-28-geological-history-of-the-peace-river-arch.htm, Accessed on 2018-10-26.

These groups also say that we are smart and adaptable, but neglect to recall that people most vulnerable to climate change's effects live in developing nations (Time - Worland, 2016).

Apart from just understanding the relationship between burning fossil fuels , releasing greenhouse gases, and radiative forcing (i.e. the greenhouse effect), there are many other signifcant pieces of evidence for why we humans are causing climate change (case 1, case 2). I'm actually quite saddened we don't hear more about these, like:

- Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations are largely driven by 'old' carbon sources (like from fossil fuels) and much less from 'new' carbon (like naturally-decaying trees).

- Certainty over small impact of other, natural, radiative forcing sources like volcanoes, natural carbon cycles, and Earth's changing orbit.

Additional reading:

(Climate) Modelling

Secondly, models about the impacts of climate change have been 'wrong' – or rather, aspects of them have been. All models carry inherent uncertainties from three main aspects:

- The data about how things are right now will never be 100% correct because we can't accurate and precisely measure everything. We have to rely on sampling, statistics, and, in some cases, best estimates.

- Models have to build in assumptions about how the world works. Sometimes, this oversimplifies relationships between variables. Sometimes, these relationships might be incorrect.

- Good models account for different scenarios that might happen. But, since no one can accurately predict the future, some scenarios won't occur.

For example, in climate modelling, even with greenhouse gas monitoring cameras, satellites, or tight regulation to measure fossil fuel usage, the data on emissions varies greatly. Even though relationships in models might not be completely correct, they are done with the greatest effort possible. In science, there are rarely 'truths' – rather, we propose theories that best explain something until we find a better explanation. And despite scenarios varying from us ending fossil fuel use tomorrow to in 2075 or beyond, they offer us insights into what might happen so we can do our best to prepare for it.

When modellers present their worst-case scenarios to the public, they do so to prepare us for the worst. When the worst doesn't happen, we should celebrate as such. But their approach not deeply flawed; modelling is not a redundant activity. Though critics are annoyed at uncertainty in estimates for things like when sea levels will actually rise, the overall trend is entirely certain. It's almost always cheaper and more beneficial to prepare for a disaster rather than meet it and fix its damages later.

Our best theories for why climate change is happening align directly with our observations, which is why there is a scientific concensus at all.

Climate Leadership

Lastly, people who resist climate action often criticize activists (in the forms of Ministers, former politicians, actors, and grad students) of contributing to climate change.

They're right – in some ways. Yes, everyone should seek to minimize their own carbon footprint. Yes, it is hypocritical to tell others to do so while not taking action yourself. But these activists are also creating change through their actions. (In the same way, Canadians cannot shy away from taking action while telling people in developing countries to do so too).

When Canada's environment minister flies to international conferences to negotiate with other countries, that can start a great wave of action. They can onset political action – Minister McKenna's efforts to solicit coal phase outs is working. They provide signals to markets about carbon pricing, and businesses are not shy to declare their support anymore (case 1, case 2, case 3). They inspire grad students to keep working away at improving climate science.

By taking steps to mitigate (and adapt to) climate change, our communities can become more resilient and more healthy.

Shifting fossil fuel use to clean technologies will:

- Make use more independent on global supply chains and avoid the geopolitics of oil,

- Inspire new industries that can secure economic benefits for the future. Cleantech in Alberta is already driving new investments and here's where Alberta aims to go, and

- Reduce pollutants in our cities and atmosphere.

Shaping our communities to be more human-friendly (e.g. walkable, bike-able) will (McKinsey & Company, 2013; CityLab – Richard Florida, 2011, TheCityFix by World Resource Institute – Banerjee and Welle, 2016):

- Fight inequality and reduce polarization,

- Encourage exercise and lead to better health while reducing the amount of energy-intensive commuting and traffic congestion,

- Greatly reduce health risks from combustion pollutants and improve safety.

- Create opportunities for more efficient resources, like district heating.

- Reduce land-use sprawl, which keep maintenance and new infrastructure costs low.

Last time I wrote a post like this, I pointed to heat as a 'low hanging fruit'. While I still maintain all of what I said, this time, I want to focus on another personal action we can take as consumers.

Numerous studies have examined the greenhouse gas impact of livestock and compared it to eating a plant-based diet. The most recent, and one of the most major, of these was published this month. Their main conclusion:

Huge reductions in meat-eating are essential to avoid dangerous climate change (The Guardian – Carrington, 2018).

The authors examined population and income projections, current levels of food loss and waste, the implications and effects of dietary change, and potential technological and management innovations in agriculture.

Their model found that global eating habits could alone compromise efforts to avoid climate catastrophe, and that, for example, beef consumption needs to fall by 90% in western countries.

Springmann, M., Clark, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Wiebe, K., Bodirsky, B. L., Lassaletta, L., … Willett, W. (2018). Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature, 562(7728), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0594-0

Unfortunately, the paper is behind a Nature paywall, but the Guardian link above provides a great overview. Its visualization about how much less of each type of meat even reach into the supplementary data from the published journal article.

Perhaps in response to the alarm raised by this publication, an American professor of Animal Science at the University of California, Davis wrote an article saying that the livestock industry should not be blamed for the climate crisis and that fossil fuel use, especially in the transportation sector, is responsible. My reponse to that article is here.

My Favourite Vegetarian/Vegan Recipes

I posted about this very issue on social media last week, where many of my friends followed up on my offer of recipe suggestions. Ideally, I would write another whole post about that, but here's a short list:

- Coconut Curry Soup – Thug Kitchen (Explicit)

- Tofu stir fry – but with dried/firm tofu like this from Minimalist Baker

- Spicy Dahl – like from All Recipes (to save time, I usually stick to just curry powder, onions, garlic, and lentils)

- Vegan Ramen – in my own style, but similar to this Minimalist Baker recipe

- Tomato and baby bok choi noodle soup – in my dad's style (with some pickled 'mustard' and cabbage)

- Stovetop Herb Popcorn – Thug Kitchen (Explicit)

Most of what I cook is from experimentation and my own intuition. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it doesn't stray far from what my parents made at home.

On my homepage, I have a map that lists my favourite food places (and attractions) with more much more diverse options in different cities around the world. For some of them, I also included my favourite dishes. The list is definitely not up to date though! In general, when I go out to eat, I typically look for vegetarian/vegan-specific, Indian, Thai, Ethiopian, Lebanese, Mexican, and Vietnamese restaurants.

Happy Cow is my go-to reference for eating out and Google/Yelp back up my options. I paid for the Happy Cow app (C$5.50 now), and it has offered some amazing choices and saved me quite a few times all around the world!

Travel and Flying

Lastly, I want to highlight why flying is also a risk that could mean we miss our global emissions target too (Peeters, 2017). To be honest, in writing this post, I needed to re-calibrate my perceptions of the impact of flying, but I'll get to that. Firstly, there are two main points I want to discuss:

- The civil aviation sector is growing at a climate-unsustainable rate because flights are becoming cheaper and people are becoming wealthier worldwide (Peeters, 2017).

- In the discernible future, planes will continue to fly on hydrocarbon fuels either from refined fossil fuels (the vast majority) or biofuels (processes so far have been inefficient and land-intensive; biomass waste conversion is not scalable to serve the aviation sector).

Peeters, P. (2017). Tourism’s impact on climate change and its mitigation challenges: How can tourism become ‘climatically sustainable’?TU Delft University. Delft University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:615ac06e-d389-4c6c-810e-7a4ab5818e8d

Flying today is responsible for around ~3% of total global emissions (Lee et al., 2009; IPCC, 1999). Low-cost airlines are shifting tourists' habits to take shorter holidays while also flying longer distances. Clearly, these trends all mutually reinforcing.

So, what can we do and what is being done?

Solutions

Unlike other transportation sectors that are starting to incorporate carbon pricing, most long-haul flights are not subject to carbon pricing on fuel. For example, Alberta only applies the carbon tax to flights within the province and the European Union Emissions Trading System similarly only applies to inter-European flights. Border-restricted aviation carbon pricing is mostly a political issue, and more international collaboration might solve this.

The aviation sector is making efforts to become more efficient too. The member states of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which is a UN Agency, agreed in 2013 to restrict growth in the sector to be carbon neutral from 2020 onwards. Their main mechanisms to do so are to use carbon offsets. New flights will have to also contribute to projects like building wind farms, using lighter paints, and improving planes' efficiencies.

But at a personal level, we consumers need to act too. When I drafted an outline for this post, I wanted to write about the emissions-intensity of flying. During my time on the University of Alberta EcoCar Team and while working for the Alberta Climate Change Office, I used the British Columbia government's guidelines for calculating emissions from different vehicles by distance (Table 11). Compared to cars, flying is certainly more intensive, which gave me a perception that it is bad in general.

However, its efficiency is actually similar to other forms of transportation. The same BC source shows flights between 463 km-1,108 km as more efficient than busses in cities. The US Federal Aviation Authority's data shows that aircraft have steadily become more efficient than all forms of transportation except rail (Yale Climate Connections - Wihbey, 2015). This was really interesting to notice and learn!

The Rebound Effect Strikes Again

Yet, the issue aviation's emissions remain. Though its efficiency has improved, its curse is that airplanes is being used for travelling further and more often than before. In a previous post, I talked about Jevons paradox, or the 'rebound effect', where improving the efficiency of using some process causes more of it to occur. As flights have become more fuel-efficient, low-cost carriers have enabled consumers to travel further and more often than ever before (Knowledge@Wharton, 2017).

Indubitably, we consumers need to travel less and shorter distances. While it may be exotic to fly to another continent, we need to recognize the impact of doing so on the planet.

Though there are many valid reasons for flying intercontinentally (including as discussed in section 2 of this post), we as consumers can purchase carbon offsets too. On my way to The Netherlands, I noticed that Air Canada is now more prominently offering as such. When I was in the UK two years ago, all my trains gave the same option.

In another post, I'll explore these markets. Not all of them deserve your attention; certain carbon offset markets are more effective and trustworthy than others. I've been calculating my personal carbon footprint for this year and am going to offset my emissions before the end of the year.

I'm glad Canadian policy-makers are talking about the climate crisis, including in an emergency debate this month in Parliament.

The federal Liberal Party's Pan-Canadian Framework is not on track to meet our Paris obligations either. The Alberta New Democrat Party's Climate Leadership Plan is fantastic... except for the ridiculously high cap that is actually set for absolute emissions from the oil sands sector (100 MtCO2e cap vs ~70 MtCO2e oil sands already emit today).

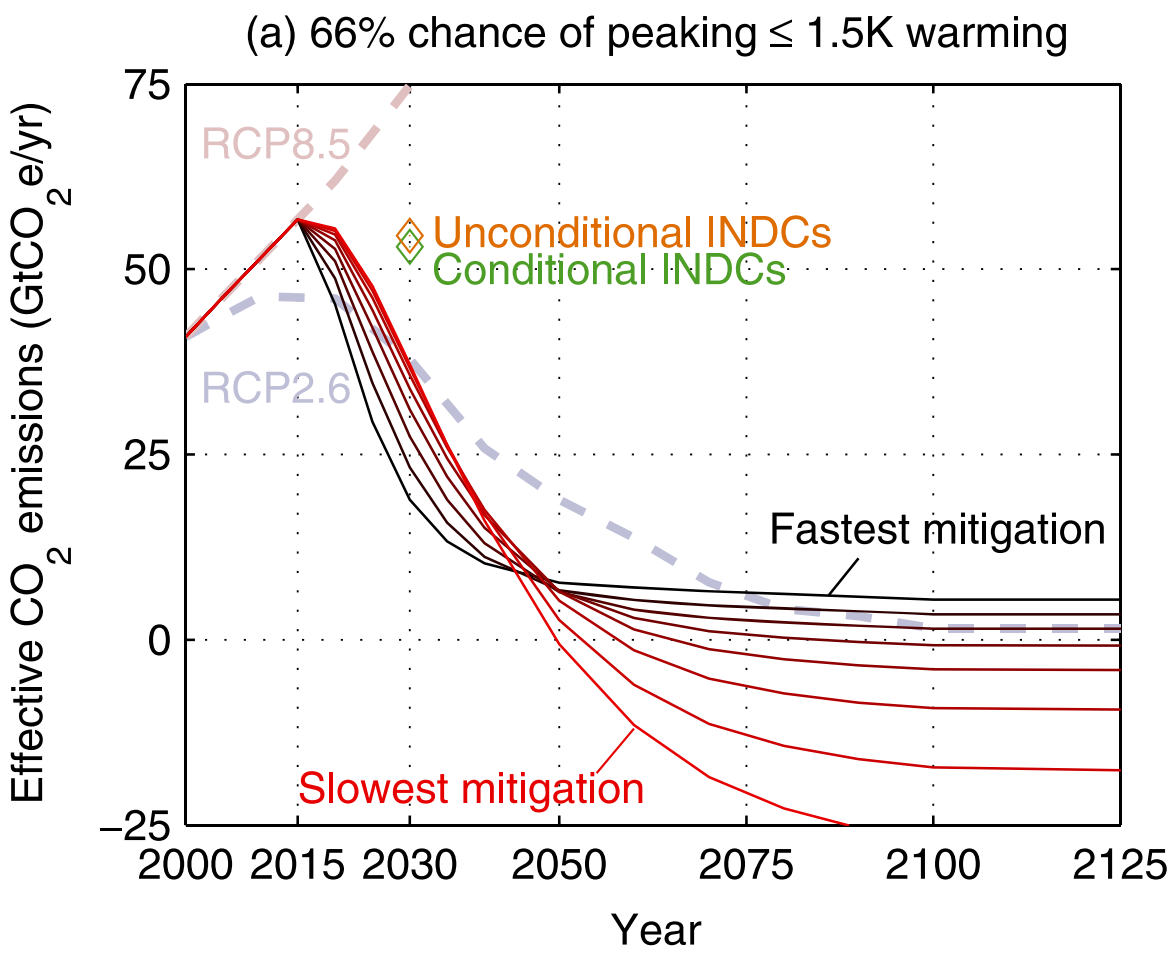

Of course, as governing parties, they face policital sensitivities, but our future (not to mention future generations) depends on the decisions that we make in the next 12 years – we need to reduce our ~55 GtCO2e/yr emissions to 35 GtCO2e/yr while doing everything we can to implement innovative technologies that don't exist yet (see this posts's introduction).

However, I'm especially frustrated at politicians who are only criticizing current policy options without offering other meaningful ideas. Alberta's provincial elections and Canada's federal elections are both next year. Who we empower to govern is going to have immense power over whether we meet Canada's obligations to mitigating the global climate crisis.

As of writing, neither the United Conservative Party (UCP) nor the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) have any policy other than "repeal the carbon tax" and push large emitters to reduce their emissions. The Alberta Party's most recent announcement on the matter is that they will only repeal part of the tax and follow a similar line as the UCP and CPC with large emitters.

This won't work.

In Alberta, large emitters are already regulated and incented to reduce their emissions without comprising their competitiveness in markets outside of the province. Stricter regulations can only mean these emitters will have to scale down, which largely means shrinking the oil and gas sector in Alberta.

Last Thoughts

Since I was in elementary school, I've been thinking about the climate change crisis and my footprint on the world. Part of why I am here pursuing an M.Sc. in Engineering and Policy Analysis is to better understand our society and tackle this very issue.

My problem looks directly at global 'grand challenges' and combines social science and engineering techniques to analyze and work towards solving them. I will always be open to discourse and tips for more things to learn about. I'd love to hear your thoughts.

But, please be quick. My friends know I am optimistic, but I too am starting to feel the heat (excuse the pun) of the urgency of the issue.

12 years.

There are only 12 years left until 2030.