Thesis Journey Part 1: Looking for Research Purpose

What are you doing there?

When other people ask me this, I usually give the spiel of what my program is about, how it relates to my interests, and how TU Delft's philosophy is unique from other schools around the world.

But now, it has become time again for me to think about this question. Am I studying for a masters an ocean away from my friends and familiy and my professional networks to learn skills, to gain some different perspectives, or just to get some more initials after my name? I mean, technically, all of the above are true, but to me, the main reason is to do as much as I can to tackle the climate crisis – use my skills as effectively as possible.

What follows below is a linearlly organized flow of thought straight from my head onto this keyboard. I'm writing this to help me structure my approach and to answer the question above for my readers.

What's important to solve in climate?

I gave a presentation about this very topic last week (interactive, PDF) and in previous blogs, so won't go over it in detail here (maybe, given the interest in the presentation, I'll turn it into a post). In short, I showed that climate action is urgent, that citizens voting and striking is hugely important to enabling policy action, and that questions still remain about how to realign our instiutions for "hard", long-term sustainability.

In my thesis work, I have been searching for where I fit in best. My technical training means I yearn to provide better information, but I also know that communication and education are even more important to turn information into action (more on this later). In fact, my hope is that blogging my thesis journey will help others understand my approach to research, tackling the climate crisis, and to life.

Still, I'm ultimately bounded by needing to deliver some technical work for my program, and there are still huge questions that analysis can help answer. SPOILER: Technical methods can also make communication and education easier.

But the same issue can be taken the other way. Why haven't politicians committed to the level of political change that we need to manage this emergency?

Lacking substantial evidence, I have come to the following conclusions from my experience and others' anecdotes. Climate policies require rewiring industries, economies, and ways of thinking, which are:

- hard to imagine

- uncertain in impacts, and

- easily politicized.

Even with substantive evidence of why an existing policy (or lack thereof), my experience has taught me that humans are reluctant to change unless they can identify specific possible futures (visions) and become confident that those visions will be more successful than the status quo. Not knowing impacts can expose one to political backlash (e.g. what if a carbon tax didn't work or was excessively destructive? (It's not.)).

Exploratory Modelling

At TU Delft, one of the policy–modelling paradigms we follow is called exploratory modelling. In contrast to traditional forecasting approaches, we recognize that there are not only numeric uncertainties in our understanding of the world but also structural ones too.

For instance, do firms embrace sustainability to attract more consumers, or do consumers demand change from firms (Which came first? The chicken or the egg?)? Depending on which method you incorporate into your model, you may find different results. And, of course, there is much we do not know about the future, and there is much we disagree on regarding how the world works. The two competiting narratives for how money is created and drives economic and innovation growth lead to contradictory recommendations for climate investment (Mercure et al., 2019).

In that light, I have thought about how exploratory modelling under deep uncertainty might be able to provide glimpses of how future pathways might unfold. This methodology can also be used to find robust policies that work across multiple possible future scenarios and even determine dynamic policy pathways that adapt to how the world unfolds.

With such insight, political advisors and decision-makers could potentially identify political sensitivities ahead of time and, combined with understanding the impacts of lack of action, could become emboldened to step forward and raise their policy ambitions.

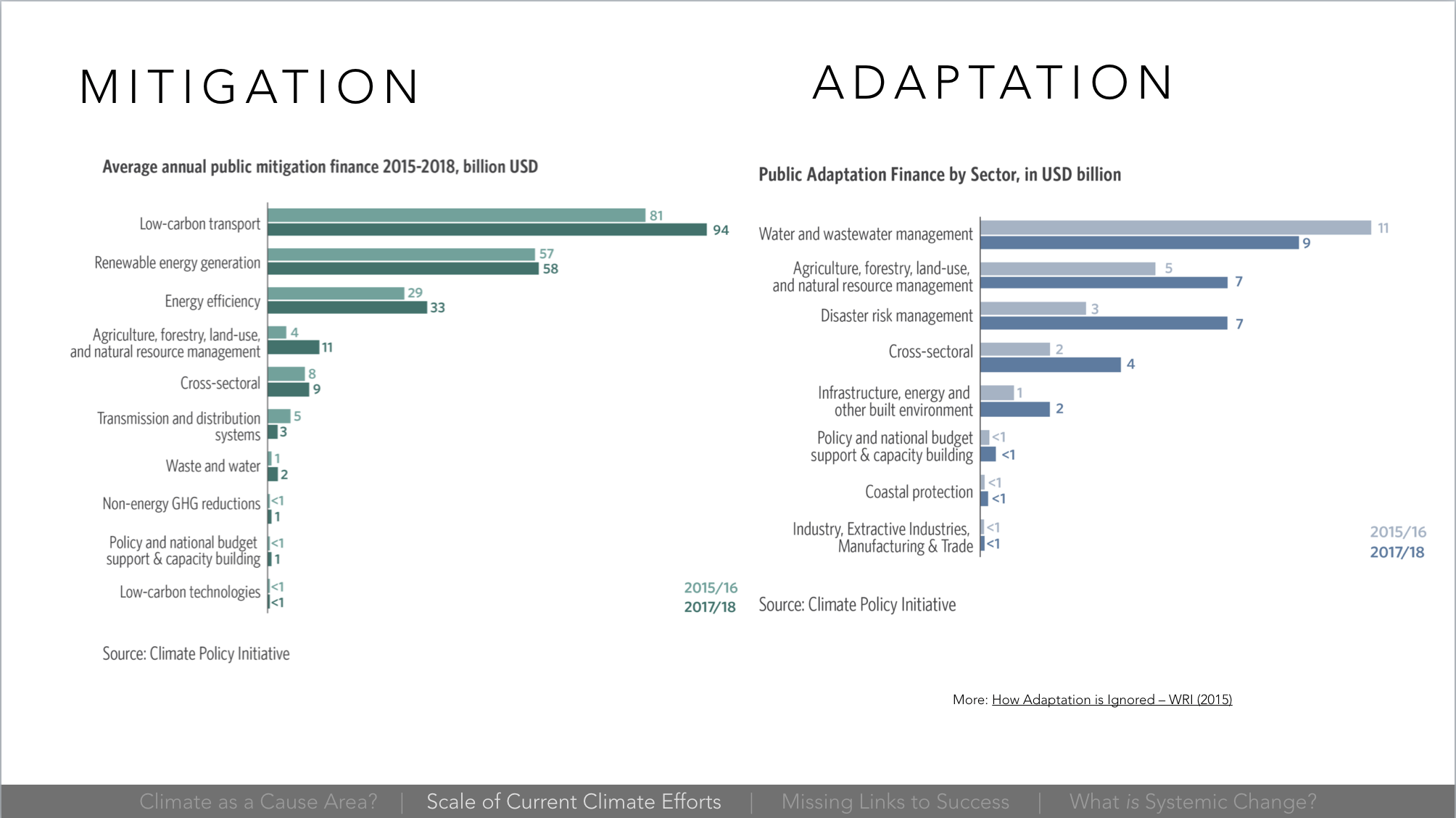

The Favourite Child: Mitigation or Adaptation?

The next question to address is if I should focus on climate mitigation or adaptation. In my time in Alberta, I recognized the lack of focus on adaptation – we still allowed flood victims to rebuild their houses in floodplains, for example (and we're still struggling to overcome our reliance on technology as opposed to behaviour change – see more on Canadian flood prevention efforts here).

Whether or not we reach Paris Agreement goals, climate change has already had devastating impacts and will continue to challenge society.

Some argue that instead of trying to prevent the inevitable, we should focus our efforts on building resilience "on the ground" so that communities will be able to shoulder the impacts of climate change when they come. Building resilience could be cheap too, especially if it is done dynamically.

Such an approach is ostensibly robust to uncertainties about the future, but I find it difficult to reconcile with issues like how multiple communities will (not) act together and how to scale resilience across communities. What is in the best interests of one city might harm another. Regionalism is the opposite of the collective action necessary to overcome the climate crisis in a way that minimizes suffering and conflict.

Can Grassroots Grow Without a Field?

Another dichotomy is top-down and bottom-up (grassroots) initiatives. In the former, the national or provincial governments would determine some strategic direction and tell the smaller governments within its region to follow it. The latter sees initiatives started by citizens or local community groups that coalesce into larger action.

In the United States, as the Trump administration declared its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, businesses, cities, and states declared they would report directly to the UNFCCC instead. Carbon pricing in Canada is similarly fragmented. Alberta removed its own policy and pushes back against the federal policy; provinces that do not have their own (that is deemed sufficient) have the federal one imposed.

Elsewhere in the world, cities have been banding together through initiatives like C40 Cities, 100 Resilient Cities, CitiesIPCC, and the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (which produced the Edmonton Declaration). These are all knowledge sharing platforms and accountability mechanisms to prepare the world's largest cities for climate change. Combined with the ongoing worldwide rural–urban migration, cities are becoming increasingly important in climate decisions. They can make decisions faster on many topics, but lack the authority and power to launch larger change. Similarly, youth and community groups have been rallying around the topic of climate action through education and strikes.

Just like in government decision-making, where grassroots are more easily managed but harder to scale, analysis for policy-support has learned that participatory processes are much more effective in convincing decision-makers or clients about the usefulness of the analysis. Edmonton and Leeds's respective citizen juries on climate action are good examples of this (combined with citizen engagement). And while top-down policy might require more negotiation and face more barriers, it can be much more authoritative.

My ability to facilitate a hands-on participatory project is limited in a few ways. Firstly, this thesis is an individual project. Secondly, my closest and more relevant contacts are in Canada. Thirdly, any relevant Dutch connections would likely want to operate and receive deliverables in Dutch. Fourth, there are ethics board considerations, where my scantily-thought out methodology would be difficult to defend. But, if I can deliver a proof of concept of a method that allows participation, I can follow up my research in the future with participatory work!

Thus, the most realist approach is follow a top-down approach and then pair it to grassroots work later (or in smaller ways during my thesis). I will try to prepare a field for seeds, which I will plant some now and do more thoroughly later.

The Objective Analyst Fallacy

Jason, you're a scientist/analyst. You must be objective and not driven by ideology and biases.

The field of economics is starting to give up the idea of Homo rationalis, or the idea that people behave perfectly rationally in their own self-interest. Instead, overwhelming evidence has shown that people are biased and often altruistic. I think that the policy world must accept a similar perspective.

Every analyst is also a human, who will have emotions and be biased by their environment. Most analysts have completed post-secondary education, which imprints a unique style of thinking on its students. The classes that students take, the order in which information is introduced, the topics of their professors' research, etc., all shape how graduates perceive the world. Sure, this often means a liberal or progressive view on the world (though environmentalism is fundamentally quite a conservative perspective), but it also comes with a rationalist imprint where, sometimes, the world's complexities cannot be rationalized. The scientific status quo also promotes reductionism, though complexity and post-normal science are also developing.

The point is that we can separate the idea of bias with credibility. If we accept that everyone is biased (which we are), then what constitute's a person or a study's credibility?

In my view, being absolutely transparent about assumptions and limitations is a great start. Working on a problem with a client (participatory) can offer them insights into how and why an analyst makes assumptions and the limitations of the study apply.

As one professor I met put it, what is the point of doing science if you don't wish for it to be used? Science is mission-driven already. Grants surround topical subjects, researchers work on what gets them out of bed each morning, and interested students are inspired by interesting topics.

What is Achieveable?

That leaves us with... what is achievable for me to do? Given all these constraints I have identified above, what's a useful issue to explore?

Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs)

IAMs are models that combine the climate, economic, and human activity considerations together. For instance, they would extent a normal fossil fuel production and consumption to see the effects of oil prices on manufacturing and transporting phones, and how those latter activities emit greenhouse gases. Carbon Brief has a great article on these, so I will refer interested readers there for more information.

Unfortunately, because these models include so many considerations, they are run at low resolutions and with few scenarios. To limiting the analysis in such a way, modellers must introduce bias when they aggregating regions and scenarios of analysis to what they suspect is likely or important, which could miss valuable insights too (Lamontagne, 2018). Even still, it takes supercomputers that cost millions – or even billions – of dollars to run.

Often, these models are run as optimization models to find the lowest-cost policies. However, they can also be run as simulation models too that simply look at outputs.

Gap Between National and Subnational Policymaking

The nature of contemporary nation-states means that policymaking is fragmented. Nations negotiate with others and also internally. Provinces or states (where they exist) rarely participate directly at the global level, so treaties like the Paris Agreement do not really consider things like which regions are oil producers or coal miners. Such issues are left for nations to work out internally.

In the western countries I've worked in, that usually means the nation sets and agrees to broader (or vague) goals and then negotiate within their own country to figure out how to best reach those goals. Unfortunately, such a division also means that there are barriers between each level of government: communication, coordination, information sharing, etc.

What is deemed as possible at the national level might be seem as unrealistic at the municipal. It is easy for someone who has a "bird's eye view" of a system might not understand the nuances of the details. It would be great to understand the impact of policies on subnational regions and how different regions' decisions might affect others.

What's a good example of something important to see? Perhaps a national decarbonization strategy might call for all households to become net zero by 2030, but an electric heat pump is grossly less efficient there (like in northern climates). In many cases, this type of insight is easy to see. But many approaches have broader impacts or require wider cooperation within a subnational region. If Utrecht decides to eliminate household methane consumption, then pipeline capacity could open up to transport other gases like carbon dioxide or hydrogen for storage or trade. It might also mean that trade economics might reverse because transportation costs drop. Canada's Line 9B is an analogous example, though that decision also had to do with oil market changes.

Another example of how subnational decision-making affects larger goals is that decisions made in one community might affects others. If one city says that they cannot shift away from fossil fuel cars because of their vast suburban neighbourhoods, then another city would have to make up for their inaction. If one region says their economy cannot decarbonize quickly, the others would have to decarbonize more.

This discussion quickly becomes political, but it is the same type of behaviour that is seen at the global negotiating table. For all parties, seeing more information earlier could alleviate policitization of issues or support proposals that could deescalate conflicts.

Downscaling

Since IAMs are built for regions, they provide little information for local decision makers. Downscaling is the idea of taking those low-resolution models and extracting high resolution insights from them. I can think of two main reasons for doing so: improving the level of analysis, and making insights more accessible for smaller governments.

Some methods for IAM downscaling have been done in the past, but only once for energy and never for economic indicators like employment (that I could find). No approaches to-date have downscaled insights by economic sector either.

Local energy and economy models exist, but not every jurisdiction has the capacity to build them or the means to pay for external experts to do so. Some might not even be aware that such an approach is possible, or might feel that modelling might not add much value to their decision-making process.

Downscaling is inherently difficult. Disaggregated information is almost akin to creating new information. The methods that exist are mathematically simplistic to be flexible. Even though they might make assumptions that are unrealistic, it might be easier to justify making one large assumption than many smaller ones. Even still, downscaling could turn systems with high (or deep) uncertainty into even more uncertainty. Some have called this a "cascade" or "explosion" of uncertainty (Dessai and van der Sluijs, 2007), which I find intuitive to visualize.

Synthesis

I've reviewed above how a modelling approach can provide very interesting insights for decision-makers, especially when paired with DMDU methodologies. Some DMDU insights need not be considered at the subnational level, but I can add value by revealing some of those. Similarly, I can add value by making this type of modelling work more accessible.

Downscaling for economic indicators could be useful for many further types of analysis. I still need to figure out exactly which indicators are most important to know. Employment and politics are a cliché as old as time, but extrapolating employment from sectors that might not even exist yet is another another layer of uncertainty to brick on top of others that I already have to wrestle. Still, it could be done – there has been work on understanding how jobs relate to new industries, like renewables. This approach could enable policy-makers to better plan for just transitions. If they can see the impacts of policies on employment in a sector and in different parts of a country, they can better plan for retraining and re-employing workers.

But ideas like reducing working hours or even replacing employment with more leisure and universal basic income are not just within "economic degrowth" (intentionally downsizing our economic activity to fit our resource use back within environmental boundaries), they have been brought into mainstream political conversations in the US by the Democratic Party's presidential candidate race.

Understanding changes in the cost of living could be hugely important to cities whose economies are changing rapidly, but a similar issue of uncertainties persists. I have no intention to model housing markets as a part of my analysis, but perhaps my work could make it easier for others to do so.

Extending Sferra et al.'s 2019 work on downscaling energy into sectors could add valuable information into how specific technologies and their pathways would look at different levels. IAMs already include many of these sectors, but their methodology left it out (mostly due to data and uncertainty reasons, I believe). I could also contrast their downscaling method with those from others, like as inspired by Gidden et al. (2019).

Conclusion

Modelling for policy analysis and to support decision-making is widespread and important for handling the climate crisis because of its massive complexities and uncertainties. It is useful to connect work done at a global level with national and subnational policy and politics. Downscaling integrated assessment models' outputs by subnational region and into economic sectors could have two main benefits. First, it could illuminate boundary conditions, required ambition, and spatial disparaties that local decision-makers could use to contextualize and evaluate their work and bring to negotiations with stakeholders and neighbours. Second, it could increase accessibility to information, which could empower disadvantaged or neglected regions to be a more active participant in negotiations with others and to guide and educate their own citizens through participatory processes. I will venture down a path to try and make downscaling more accessible while assessing the approach's validity. If such an approach is feasible, it could be paired with many other types of considerations and improve policy-making for the climate crisis.